or Exactly Why Apple Keeps Doing Foolish Things

Apple keeps doing things in the Mac OS that leave the user-experience (UX) community scratching its collective head, things like hiding the scroll bars and placing invisible controls inside the content region of windows on computers.

Apple’s mobile devices are even worse: It can take users upwards of five seconds to accurately drop the text pointer where they need it, but Apple refuses to add the arrow keys that have belonged on the keyboard from day-one.

Apple’s strategy is exactly right—up to a point

Apple’s decisions may look foolish to those schooled in UX, but balance that against the fact that Apple consistently makes more money than the next several leaders in the industry combined. While it’s true Apple is missing something—arrow keys—we in the UX community areN missing something, too: Apple’s razor-sharp focus on a user many of us often fail to even consider: The potential user, the buyer.

Bruce Tognazzini was hired at Apple by Steve Jobs and Jef Raskin in 1978, where he remained for 14 years, founding the Apple Human Interface Group and designing Apple’s first standard human interface. He is named inventor on 57 US patents ranging from a intelligent wristwatch to an aircraft radar system to, along with Jakob Nielsen, an eye-track-driven browser.

During the first Jobsian era at Apple, I used to joke that Steve Jobs cared deeply about Apple customers from the moment they first considered purchasing an Apple computer right up until the time their check cleared the bank. Of course, in later years, the check was replace by a credit card, and check clearance was replaced by the 15-day return period, but Steve’s and Apple’s focus remained the same.

What do most buyers not want? They don’t want to see all kinds of scary-looking controls surrounding a media player. They don’t want to see a whole bunch of buttons they don’t understand. They don’t want to see scroll bars. They do want to see clean screens with smooth lines. Buyers want to buy Ferraris, not tractors, and that’s exactly what Apple is selling.

The tipping point

While Apple is doing a bang-up job of catering to buyers, they have a serious disconnect at the point at which the buyer becomes a user. That same person who was attracted to that bright and shiny computer in the showroom, as opposed to those dull-looking things in the Microsoft look-alike store, may not be so happy when denial breaks down, and he admits to himself that it’s so bright and shiny that the reflection of his office is blocking out the image on his screen.

(Steve had a habit of setting up impossible tasks for his people, only to have them overcome them anyway. This year, Apple release the latest round of bright and shiny monitors except they don’t reflect the office to the exclusion of the screen. 75% reduction in reflections and just as glassy smooth. Some kind of magic.)

But let’s talk about software. Let me offer two examples of Apple objects that aid in selling products, but make life difficult for users thereafter. Then I’ll talk about a simple, zero-downside solution that would solve the unnecessary problems Apple has been making for itself before presenting a very valuable lesson the rest of us can learn from Apple.

The Apple Dock

The Apple Dock is a superb device for selling computers for pretty much the same reasons that it fails miserably as a day-to-day device: A single glance at the Dock lets the potential buyer know that this a computer that is beautiful, fun, approachable, easy to conquer, and you don’t have to do a lot of reading. Of course, not one of these attributes is literally true, at least not if the user ends up exploiting even a fraction of the machine’s potential, but such is the nature of merchandizing, and the Mac is certainly easier than the competition.

The real problem with the Dock is that Apple simultaneously stripped out functionality that was far superior, though less flashy, when they put the Dock in. The Mac is a powerful computer with lots and lots of room. There was no reason to strip anything out. The flashy-demo Dock object and the serious-user objects could and should have continued to coexist.

Invisible Scroll Bars

“Gee, the screen looks so clean! This computer must be easy to use!” So goes the thinking of the buyer when seeing a document open in an Apple store, exactly the message Apple intends to impart. The problem right now is that Apple’s means of delivering that message is actually making the computer less easy to use!

When we were first implementing GUIs at Apple in the early 1980s, scroll bars were primarily an input device: Any document you saw on your screen was likely one you had written, destined eventually to be printed and distributed. Today, most documents are web pages or email you’ve never laid eyes on before, and the scroll bar has become a vital status device as well, letting you know at a glance the size of and your current position within a document.

Hiding the scroll bar, from a user’s perspective, is madness. If the user wants to actually scroll, it’s bad enough: He or she is now forced to use a thumbwheel or gesture to invoke scrolling, as the scroll bar is no longer even present. However, if the user simply wants to see their place within the document, things can quickly spiral out of control: The only way to get the scroll bar to appear is to initiate scrolling, so the only way to see where you are right now in a document is to scroll to a different part of the document! It may only require scrolling a line or two, but it is still crazy on the face of it! And many windows contain panels with their own scroll bars as well, so trying to trick the correct one into turning on, if you can do so at all (good luck with Safari!) can be quite a challenge.

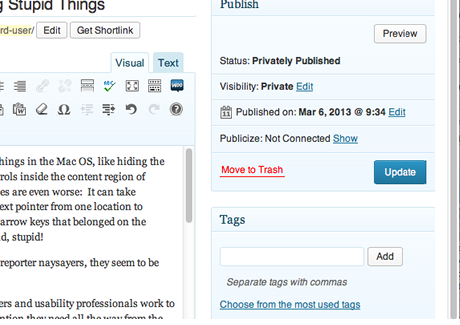

This article in WordPress editor in Safari with Mac set to “Alway Show” Scroll Bars

(The scroll bars, even when turned on, are hard to see with their latest mandatory drab gray replacing bright blue and are now so thin they take around twice as long to target as earlier scroll bars. When a company ships products either before user testing or after ignoring the results of that testing, both their product and their users suffer.)

One might argue that eye-tracking could be used to turn on the scroll bar as needed, but let’s consider that: In the above example, if the center scroll bar suddenly hove into view every time your eyes wandered between the left and right columns, it would be more than a little distracting. OK, so then maybe we force the user to stare fixedly at the place the scroll bar should appear for some set amount to time. Hey, now there’s a bad idea!

Fortunately, the answer to both these and other problems is much simpler and needs no such sophisticated technology as I will soon reveal (I promise). First, however, let me present a new model.

The User Spectrum

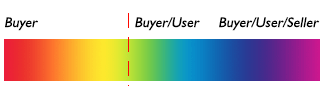

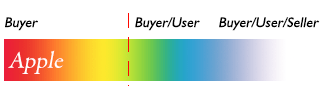

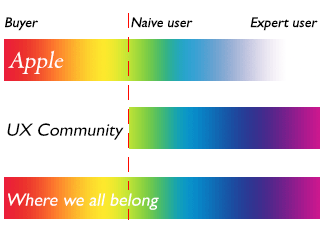

The UX community generally considers users to be arrayed along a spectrum that stretches from naive to expert. Apple expands that array by prefacing it with buyers. The following chart shows that more complete spectrum, flowing from the buyer before the sale, through the dashed red line at the point of sale, and then moving along from naive to expert user with the continuing passage of time.

Supporting “The Third User”

Apple has concentrated virtually all their effort on potential users—buyers—and new users, leaving out, in the last several years, experienced users almost entirely. The User Experience (UX) community are in the opposite position, rarely considering our user’s wants, needs, or desires until the moment they first open their newly-purchased products.

Both our efforts should resemble the third line on this chart, with all of us properly supporting people through a continuum stretching from customers’ first faint desires to the point at which they’ve become seasoned professionals.

Industrial Design: The Source of Apple’s Secret

Apple has drawn from the lessons of industrial design, applying them not only to external hardware, but software as well, a brilliant step forward that has made their products as appealing when turned on as when turned off.

Industrial design & “the message”

A primary purpose of industrial design is to deliver a carefully-crafted message. Let’s look at two products, the tractor and the Ferrari.

“I am powerful, and I should like to remove your arm”

The raw form of a tractor delivers a simple, brutal message: “I am powerful!” Unfortunately, people often see an unwritten message accompanying it, such as “I should like to remove your arm,” or simply “I’m way too powerful for the likes of you!”

“I am amazingly fast, and you are devastatingly attractive.”

A Ferrari also delivers a power message, but not by displaying its engine. Instead, the Ferrari’s message is indirect, rather than direct, the hallmark of industrial design. The reality of the Ferrari’s powerful drive train is entirely hidden, skinned over with a second, completely independent message in shaped steel that not only screams power, but adds in the promise of speed, fun, and the granting of an instant increase in physical attractiveness to those who would possess it.

The reality and the message are truly independent. A sleek Italianate body could be gracing a Volkswagen Beetle chassis, and, as long as the buyer never made the mistake of turning the key in the ignition, the message would continue to ring out loud and true. What you are seeing in the photo above is actually a Sterling Nova composite body. The Nova, a design inspired by the Lamborghini Miura, was developed in England as an after-market body kit for bolting to, yes, a Volkswagen Beetle.

Industrial design: Borrow the aesthetic, ignore the limitation

While Apple has copied over the aesthetics of industrial design into the software world, they have also copied over its limitation: Whether it be a tractor, Ferrari, or electric toaster, that piece of hardware, in the absence of upgradeable software, will look and act the same the first time you use it as the thousandth time. Software doesn’t share that natural physical limitation, and Apple must stop acting as though it does.

Apple need change nothing about their support for buyers and very little for new users. They need only add support for experts, and they can do so without any effect whatsoever on either of the first two groups.

If Apple’s goal is to sell computers by having the interface look clean in the store, there’s no reason the interface need remain obscured after the sale. As soon as users get home and register, the software can flip the option to display scroll bars to Always, triggering the start of a gradual, planned transition from training-wheels to full-fledged computer-user. That’s good and proper design.

What we see as clutter (known as “noise” in Information Theory) when we look over someone’s shoulder is often a screen with a high concentration of information meaningful to them. If your personal aesthetic by nature or by training is tuned to seek visual simplicity, you may find that distressing. It is our job to remove real clutter—any tools or data not needed right now—but it is not our jobs to hide what experienced users need just to make ourselves feel better when we look at their screens.

The cost to Apple for ceasing to support expert users is spilling over into lost hardware sales. I myself have stopped buying both new iPads and iPhones because Apple’s increasingly powerful hardware is so badly crippled by its software. Having shot more than 20,000 digital photos, I’d like to access them on my iPad from memory, lots and lots of memory. Not going to happen. Why? because when I transfer my photos, Apple strips off all my titles, date, time, location info, and keywords, then randomly shuffles all my folders. Individual photos are impossible to locate should I carry around more than 100 or so. I already have plenty of memory for 100 photos.

Last year’s buyers, so confused by what a pinch gesture was or how use a trackpad, have become expert over the next twelve months, ready to move up to the next level. In fact, there are millions of these now-expert users. Inside Apple today are employees who understand that. These same employees understand that shipping a product like Aperture that, after almost five years, is still not even feature complete and is rife with data-destroying bugs, is a bad idea. That having a flagship computer that has been obsolete for four years makes the entire company look bad. However, in recent years, their voices have not been heard.

Apple’s upper management probably lack the time to become expert users themselves. They need to start talking to people who are expert users. People inside Apple. People like me who have been in and around Apple for the last 35 years and, being expert users as well, understand the issue. (I’m available to anyone at Apple that would like to talk privately.)

Apple’s upper management needs to start listening to people in the press who keep writing article after article questioning why Apple refuses to let people select a “real” keyboard from the open market for their mobile devices if Apple won’t supply one with arrow keys, etc.,

Dear Apple,

We wouldn’t keep jail breaking your phones by the millions if you were giving us what we want and need,

—Your Loyal Users

Apple’s market research has already been done for them: Millions of users jail-break their iDevices to get at missing functionality. Apple need only look at what users are installing on those jail-broken phones to know know exactly what experienced users are craving. Sometimes the jail broken solutions are brilliant and should be bought and incorporated. Sometimes they’re clumsy, but nonetheless serve to illuminate unmet needs.

There’s no reason in the world not to grow all Apple’s devices to meet the needs of users as they grow. It is only playing into competitors’ hands, hurting the very people Apple courted last year and the year before when they were new buyers instead of expert users.

It’s good to have a walled garden, but the walls have to be far enough apart not to crush the child as he or she grows. As the naive user hits their “teenage years,” they should have the right to make their scroll bars any color they want, not drab gray because that’s “in” this year. If the user who’s now an all-grown-up expert favors productivity over visual simplicity, that user has the right to select a keyboard that’s actually functional. Even if the user wants to select a keyboard that’s provably less efficient, as the USS Saratoga was, that is still the user’s right (as much as it pains me, as a human-computer interaction designer, to say it).

The Buyer-User-Seller Spectrum

Earlier, I showed buyers becoming users and thus, by implication, ceasing to be buyers. Actually, buyers never cease to be buyers. True, you have their money, but they can leave you in an instant. Unless you never want to sell to them again, you should continue to consider them buyers. They do make a transition to user, and they also make another important transition: They eventually become a key part of your sales force.

If you keep your customers happy, they will become unpaid ambassadors for your product. Or, conversely, unpaid disparagers of your products. Ask yourself, what do you put your own faith in, manufacturers’ puffery or experienced users’ amazon reviews?

Apple’s expert users are their largest, most influential sales force. By allowing support for expert computer users to languish over the last several years at the very time that they’ve been adding to the ranks of expert computer users, Apple has slowly been turning its largest, most influential supporters against it.

Apple has been shipping mobile devices for years now, but they’ve refused to allow their users to move beyond the barest naive-user stage. People don’t lose 50 IQ points when they pick up a mobile device. When they set up an appointment on an iPad vs. a computer, they still want to set an alarm for 1 hour and 40 minutes beforehand, not be forced to choose between either one hour or two hours because someone at Apple decided a minute-changing interface would be too complex. Perhaps it would be for demoing purposes, but it makes experienced users feel as though Apple thinks they’re stupid. You might be able to get away with a lot of things with your customers, but calling them stupid is not one of them.

It’s not as though people haven’t been writing about it, talking about it, screaming about it. They have, each and every day for years, and not just in tech publications. It is damaging Apple’s market share, and it is killing the stock price. And it is completely unnecessary not only because it is easy enough to design an interface that will “unfold” to support users as they grow, but because, paradoxically, sometimes even buyers whom you would least expect want some complexity.

The complexity paradox

Among those who seek out complexity are people who are actually terrified of complexity, hence the paradox.

One of the keyboards I worked on at Apple we dubbed the USS Saratoga because it was approximately the size and shape of the giant aircraft carrier of that same name. It had every extra key anyone at Apple could think of, including many unrecognized by the Macintosh at the time. Its extreme size pushed the mouse further from the user, causing a time delay each time the user moved between keyboard and mouse. It was inefficient and really scary looking!

The new keyboard flew off the shelf faster than jet fighters off the real Saratoga, and it wasn’t expert users in need of all those non-functional keys buying it: It was comparatively new users—mainly guys—seeking visual evidence that their little Macs were real powerhouse computers. The buyers went for it because they found it scary, knowing that, in turn, it would intimidate their friends.

Before the invention of the personal computer, I spent fifteen years selling consumer electronics and teaching sales techniques. (I was both one of Apple’s first employees and first dealers.) I found the best way to motivate sales was to demonstrate ease-of-learning and ease-of-use while simultaneously talking about power. Apple used to do that, with its ads for “munitions-grade” computers. Now, it’s all toy-piano music and nursery-school software.

Apple has been letting Microsoft and Android “own” the power sphere for many years now. I find no compelling reason for Apple not to grab some of that space back. Visual simplicity sells and should be jealously guarded, but a certain class of complexity sells as well.

Shortly after this article was posted, Apple hired Kevin Lynch as its new VP of Technology. Kevin Lynch understands these issues I’ve been discussing, giving me hope that experienced users and, in fact, all post-purchase users will have a new and stronger voice.

What the UX Community Needs to Do

I talked a lot about what Apple needs to do, and you probably noticed almost all was argument. It is usually hard to get through to Apple, and what they actually need to change is rather simple. Members of the UX community may need to do a lot more, but I suspect far less persuading will be necessary.

Most people in the UX community have excluded buyers from their thoughts simply because the users they support don’t make their own buying decisions. I have three arguments for including buyers in every step of your design process regardless:

- Buyers will either see the software demo’ed, try it themselves, observe their users using it, or hear complaints, in particular, if users hate it.

- Users must psychologically “buy in.” You reduce training costs when software is attractive.

- Users, lately, have been buying things like iPhones on their own, regardless of corporate policy. Letting them do so then becomes corporate policy. Next thing you know, your company is out.

Samuel Johnson once remarked, “When a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.” If you begin to think of your users as buyers, too, able to cut you off without a second’s thought should you fail to please them, you will discover that little spark of fear will concentrate your mind wonderfully as well. You’ll end up with a product that is more attractive, easier to learn, and more productive because you will be motivated to make your user/buyer happy, not just efficient. (One can be miserable but efficient for only so long.)

If you’re not sure where to start with all this, begin where Apple did, with industrial design. Learn about it and then move on to motivational psychology. It adds an entirely new dimension to one’s understanding of people, a dimension directly applicable to buyers.

Become best friends with marketing. We in UX have always seen them as allies, but they should be even closer, acting as partners when we are designing for buyers. It’s time to start lurking in retail stores and eavesdropping on people dropping cash on consumer products. Find out what makes them tick. Get a sense for what motivates them.

Here is a sprinkling of books that I have found particularly useful in understanding buyers and how they fit into the spectrum of users. Start here and branch out.

| Designing for People by Henry Dreyfuss. Dreyfuss was the greatest industrial designer of the last century. He churned out everything from locomotives to cars to flying cars to the Trimline phone to Polaroid cameras to the round Westclock alarm clock to the equally round Honeywell thermostat, inspiration for the Nest. | ||

| I am a particular fan not only because he was a brilliant industrial designer, but because he understood the vital importance of usability testing to validate designs, specifically ensuring that the desires and needs of the full spectrum of users—buyers, naive, and expert—were being met. We have much to learn from him, and this book is an excellent starting point. | ||

| Henry Dreyfuss: The Man in the Brown Suit by Russell Flinchum. If Dreyfuss’s own book has whet your appetite, this well-written biography will help sate it. | ||

| While Designing for People gives us insight into Dreyfuss’s mind at the time of its writing, this biography gives us insight into his thinking as it changed over the decades, adding dimensionality. It is filled with illustrations and personal details missing from Dreyfuss’s own work. I have gleaned much from each. | ||

| Games People Play by Eric Berne. Freudian psychoanalyst Eric Berne’s Transactional Analysis (TA) altered mainstream therapy and sales psychology forever. You can apply TA’s simple, reliable model of human behavior from first field study to final usability follow-up to ensure you cover both the wants and needs of all users, including buyers. | ||

| The initial 3000 print run turned into 5 million. A fun read, it will alter your view of users forever. I’ve read every one of Eric Berne’s books and research papers. This is a perfect starting point. | ||

| “An important book…a brilliant, amusing, and clear catalogue of the psychological theatricals that human beings play over and over again.”— Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. | ||

| Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson. Yeah, that book. If you haven’t read it, you should. This man was the greatest industrialist of our time and was responsible for the creation of the most revolutionary products in our industry. | ||

| Steve Jobs was also one of the greatest human-computer interaction designers of all time, though he would have adamantly denied it. (That’s one of Apple’s problems today. They lost the only HCI designer with any power in the entire company the day Steve died, and they don’t even know it.) | ||

| Walter Isaacson was able to get further into Steve Jobs’s head than any save perhaps Steve’s own wife. It is a must-read for all of us, including those who might have thought we knew him. |

All three of these men have had a profound influence on my life for decades. I’m sure there are other people and other books of note that could help all of us to even-out our support of the spectrum of users. Please help out by suggesting more books below.

The Forum

When you visit a forum, you are visiting my home. You will not see personal attacks on myself or other writers here because Siri automatically forwards them to the writer’s mom, along with a letter of explanation. My apologies. She’s rather strict about this. My long-time editor, John Scribblemonger, will then publish comments that are on point, but may edit for brevity and clarity. This being “asktog,” I will then often chime in, even if not explicitly asked.

I hope you will find the result worth reading, as well as joining.

¡Bravo!

Thanks! A co-worker and I were just discussing the bad experience of taking a video on the iPhone. Why didn’t Apple default to horizontal capture instead of vertical capture? We always forget we need to turn the phone sideways to prevent the awful experience of capturing the video vertically, then watching the video back on a TV or monitor.

This is an interesting problem, because Apple doesn’t actually “default” to one position or the other. Users do. When taking still pictures, we naturally turn the phone to capture the image in portrait or landscape, as we choose, but with video, we often fail to even consider orientation.

I suspect a couple of factors converge to cause this. First, from the beginning of home movie cameras in 1932, the standard form factor for image-capturing devices, film or video, has always been vertical. Second, when shooting video, the user is concentrating on motion, typically aiming the camera toward the center of motion. This contrasts with still photography where the user is more likely to examine the totality of the picture, not just the center, noticing orientation. Errors in orientation are less critical in still photography as well: One can either crop a still photo or just show it in portrait mode. Cropping a video accidentally shot as 1080h x 1920v down to the proper HDTV ratio will leave you with just 1080h x 608v, a huge hit for an image to be spread across a large screen.

Apple could force orientation, by displaying nothing but an animated arrow and a message until such time as the camera is more horizontal than vertical. Less confining would be the same the arrow and message, but also turning on the camera, with the warning disappearing if the user pressed the record button, indicating he or she really did want to make a vertical movie. A middle ground would be the image being somewhat dimmed, still enabling the user to line up the shot if vertical is really desired, but deflecting the unwary from making a huge mistake. In this case, btw, the unwary could be a new user or expert user; we all make mistakes.

Meanwhile, my fellow inventor Robert W Hubrecht has suggested that websites displaying video need to capture and read the orientation metadata and enable the viewers to display vertically-oriented video properly, not just flop it on its side. I heartily agree.

I forwarded a link to this excellent critique to Tim Cook. The last 2 times I wrote his office replied so I’m optimistic.

Mmm. In the new ITunes on the Mac you can not even double click the title bar to shrink the window. What the?

This happens when the UX group fails to give the QA group a Human-Computer Interaction Checklist. If there is a UX group. If there is a QA group.

For what it’s worth, you can enable the scrollbar without actually scrolling. Just put two fingers on the trackpad like you’re going to scroll, but don’t actually scroll.

Doesn’t seem to work with my Logitech mouse :-). The trick only works with Apple devices, and not everyone uses an Apple device. Nor should they. Mice, for example, test as twice as fast as trackpads for pure pointing tasks. Gestures may short-cut some of the times that mice might require, but it’s doubtful that its enough to make up the shortfall.

Apple mice, meanwhile, are designed for selling, not using. To right-click, it’s necessary to simultaneously press down with the right finger while lifting up with the left, twice the effort, twice the stress. The heavy metal baseplate requires serious users lift an unnecessary weight hundreds of times per day for no reason other than to motivate an initial sale.

Apple needs to design and test their products for all the devices people are using.

An excellent article on an important topic!

Do you have any recommendations on how to convince other members of a team that this is important? I often receive pushback from the startups that I work with when I focus on the potential customer experience. They tend to focus on the data which they want from the user and field placement, but balk at anything which has to do with the user’s emotions (which are important when it comes to making a sale).

The words and phrasing used make a big difference. I am much more likely to enter personal information if there is a clear reason why it is needed, for example. There is also a big difference between a customer and someone who is begrudgingly a customer, especially on community based sites. When I talk about things like building trust, all I get back is “Why are you focusing on things which aren’t important?”

Do you have any advice on how to convince team members who aren’t really comfortable with emotions (both theirs and their users’) that it is a necessary part of design? I have a lot of science to draw from for things like UI placement, color contrast, etc…, but I am often reduced to hand-wavy arguments in this department.

You can start by offering them a copy of Emotional Design:

Then, read The Games People Play yourself, and maybe some follow-on books on TA, then give a one-hour talk to give people insight into two things: Not everyone is like them, and if you don’t motivate people, they will be unhappy, resulting in lost sales and lost productivity.

Tog, I really appreciate your perspective, and as usual, feel you are spot on. Before becoming an entrepreneur, I spent some times as a usability specialist without much knowledge or understanding of the buying process or the buyer itself. Now with ten years of business ownership, I have a much firmer understanding of how UX encompasses everything–it’s every touch point a customer has with a product or service. Thank you for getting the word out, as I suspect this is going to be the next area where enlightened companies will have a competitive advantage over those just now employing UCD into their products.

Very nice article, but… would you say Apple advanced users are in general not satisfied with their devices?

I have probably seen close to 250 articles expressing unhappiness in the last several years. We know that people are bitterly unhappy that Apple refuses to update their flagship computer, forcing serious users to either move to windows, struggle along with computers that are lagging far behind the curve, or pay full price for a computer lacking the thunderbolt ports available on $600 “toy” computers from Apple. Apple’s users, at the same time, are remarkably loyal, not only because both mobile devices and computers are “sticky” products, but because people love Apple and love their devices. They try their best to get along, hating the very thought of divorce. However, divorces happen, and, when they finally do, they tend to be very ugly and very permanent.

Yes. Positively. Nor will they ever be because every time the device increases in power, the range of possibilities expands with it. We always want more, and for many years Aplle gave us more. Now they’re giving us less.

Thanks for another well-written declaration of the (not so) obvious.

One comment I’d add is that beyond consumer products UXers face challenges where the “buyer” and the “user” are not just points on a spectrum but separate people. This was “drilled into me” long ago working on medical diagnostic systems where doctors and department heads are the buyers and lab techs are the users (and often with little or no say in the decision). Unfortunately demos of such systems are much more lengthy and the buyers often not involved in their day-to-day use.

I’m well aware of that disconnect. One of the saddest things I saw was when I was working at WebMD. I visited a doctors’ clinic in which a phlebotomist was stationed, supplied and paid for by the blood lab that actually performed the tests. The phlebotomist was required to stand, not sit, eight hours a day using a computer that had the monitor sitting on top of a file cabinet, with the middle drawer of the cabinet opened to allow her to lay the keyboard down across it. Neither the doctors nor the lab would pay for either a chair or desk for this poor woman. I could do nothing about the hellacious conditions under which she and others like her worked, but I made damned sure that the software she used treated her like a person, not the slave her employers took her to be. Think of your users as customers, and you won’t do in software what these people were doing in the real world.

There’s one big argument for leaving scroll bars always on—the user may not know there is more to the document than is being currently displayed. Which could be disastrous. The window should *always* let the user know if there’s more “down below.”

Yes. That’s an argument for not only leaving it on, but for making it obvious, which is why the OS X team made it the “elevator” bright blue, rather than dull gray. Even with that, documents should be designed to “break” at the bottom of the screen, with text and graphics staggered in such a way that something always looks incomplete, letting the user know with certainty that something more can be found below.

Like you I’ve been an Apple user — no, champion — since buying an Apple II for the California Legislature in 1981, its first personal computer. I bought one of the first Macs, and vowed never to return to Microsoft World. Yet today I use a Galaxy S III.

The story is more complex than simply trooping up the hill and falling down. Apple’s been on a self-destroy kick for at least a decade.

Two years ago, when Lion came out, it created havoc among Macbook users, especially MacBook Air users. My own Air’s CPU, driven to madness by Lion’s perversity — imagine trying to make a multi-thousand-dollar Mac pretend it’s a $300 iPhone! — went on overdrive and fried not only the logic board and everything on it, but also the SSDs. Apple never acknowledged my loss. Instead, it quietly replaced the burnt out parts, but still kept Lion onboard. It took me a weekend to purge my Air of Lion and reinstall Snow Leopard, Apple’s last meaningful Mac OS update.

When I brought up my Lion experience on the Apple Forums — as did several hundred other Mac users, with similar stories to tell — we were told we were delusional, bad-mouthers, or just plain uninformed. I mean, rather than invite us in as the aggrieved, but willing to help, Apple slammed the door. Eventually it was proven we were right, there were software flaws, but Cupertino never admitted it.

Shades of Microsoft. The notion that Apple and its heavy users might be at loggerheads would never have occurred to me a decade earlier.

I no longer feel an affinity for Apple — it’s just another a “device” company, no longer a computer company — or for any of its personnel. I no longer expect the mandatory innovation in a box top. Their job is exclusively to make the shareholders happy. The interface issues are indicative of how little thought Apple gives to user efficiency versus how much it’s become concerned only for the efficiency of production. When my Macs wear out (and they’re getting there), I’m unlikely to replace them with Macs. I need something less phone-like and more computerlike in return for my $2000 purchase. I hope Apple gets it soon

PS The best “Mac” I ever owned was my Motorola StarMax built during that small window in the late 90s when Gil Emilio licensed the Mac interface to third parties. It had all the good qualities of a Mac plus an interior that was at least 50% customizable. Then Steve Jobs returned, closed the window, and imposed two decades of crippling closed-system philosophy.

Tim Cook has merely continued Jobs’ monotheism, perhaps because he has nothing personal with which to replace it. A game-changer like relicensing the Max OS would create the constructive disruption necessary for Apple to get off the dime. Apples wealthy, but that’s as far as it goes. If it wants back the innovation crown, it had better start designing a better computer — where most innovation expresses itself — rather than merely building toys.